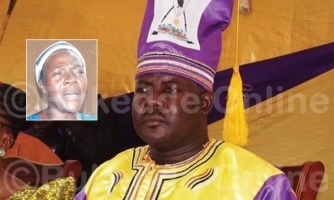

Kabaka Mutesa sent (without) packing, again

This is the second part of our special series on the tug of war between Buganda and the central government, putting this year's bloody clashes and the continuing stand-off in a historical context. The first part showed how the current conflict is uncannily similar to the clashes of 1966 and 1953. In this part, HENRY LUBEGA takes a closer look at how Kabaka Edward Mutesa fell out with the colonial authorities, and then with the Obote government, with disastrous consequences for king, kingdom and country:

This is the second part of our special series on the tug of war between Buganda and the central government, putting this year's bloody clashes and the continuing stand-off in a historical context. The first part showed how the current conflict is uncannily similar to the clashes of 1966 and 1953. In this part, HENRY LUBEGA takes a closer look at how Kabaka Edward Mutesa fell out with the colonial authorities, and then with the Obote government, with disastrous consequences for king, kingdom and country:

President Milton Obote’s attack on Kabaka Edward Mutesa in 1966 is widely regarded as the beginning of the culture of repression and use of the gun to settle differences that bedevils Uganda to this day.

The flight of the Kabaka into exile remains one of the darkest moments in Buganda’s history. Yet long before Uganda’s independence in 1962, there were already strong signs that Buganda would, at best, have an uneasy relationship with the central government. In the 1920s and 30s, the British considered forming a closer union among their East African colonies – Kenya, Uganda and Tanganyika, as Tanzania was then known.

The idea was vehemently opposed in Uganda, especially by the Baganda. They feared that the federation would open doors to European settlers, as had happened in Kenya, and that their ancient kingdom, with its treasured culture, would be swallowed up in a bigger East Africa. The idea was shelved, but not completely discarded. Following the appointment of Andrew Cohen as the governor of the Uganda Protectorate, a memorandum on Constitutional Development and Reform in Buganda was signed by the Governor and Kabaka Edward Mutesa in March 1953.

The memorandum stated that “Uganda had been and would continue to be developed as a unitary state.”

A few months later, the governor announced changes that included an increase in African representation in the Legislative Council, the Governor’s Executive Council, and having the majority of the Lukiiko members elected, not appointed by the Kabaka. These reforms were the prelude to the 1953 crisis that saw Kabaka Mutesa exiled to England. The Lukiiko was, in particular, opposed to having an increase in elected members.

However, Mutesa convinced the Lukiiko to accept the move, reasoning that it would then be harder for the governor to ignore the views of a largely elected Lukiiko. But as the tension over the increase of elected members of the Lukiiko subsided, a fresh burst of anger was stirred up by what Mutesa called a “careless remark” by the Secretary of State for Colonies, Oliver Lyttleton.

On June 30, 1953, Lyttleton, making a speech to the East African Dinner Club in London, said: “Nor should we exclude from our minds the evolution, as time goes on, of still wider measures of unification and possibly still larger measures of federation of the whole East African territories.”

There was immediate protest from Buganda, whose old fears about East African federation, and the loss of the kingdom’s special position in Uganda, were re-ignited.

“It was clear that a crisis was under way. The mention of federation in East Africa was enough to bring all Baganda anxiety frothing to the surface,” Mutesa wrote in his book The Desecration of My Kingdom.

In protest, the Kabaka agreed to the Lukiiko’s request not to nominate members to the Legislative Council.

Kabaka sent (without) packing

Mutesa, however, held confidential talks with Cohen. He writes, “We drafted what was to be seen as joint statements by the two of us, which I was to read to the Lukiiko. [I] withdrew my demands and accepted the re-assurances already given…our talks had been confidential, I had already been refused permission to tell the Lukiiko what was happening.”

Mutesa wanted to inform the Lukiiko of this tricky situation, much to the governor’s displeasure. “We had reached a curious position where Sir Andrew demanded that I should use all my power to help him implement a policy of which I disapproved as strongly as they (Lukiiko) did.”

“The struggle was now personal, courtesy collapsing. Sir Andrew was talking in threats, and he finally asserted: ‘If you don’t agree, you will have to go.’ My reply was: ‘If anyone has to go, it will certainly be you’.”

The protectorate government withdrew its recognition of the Kabaka on November 20, 1953, on grounds that he had failed to give royal co-operation to Her Majesty’s Government as required by article 6 of the 1900 Buganda Agreement. On November 27, Sir Andrew sent Mutesa an ultimatum to meet his demands. Mutesa insisted on consulting the Lukiiko. Three days later, on November 30, Mutesa was given deportation orders.

“I asked if this meant that I was under arrest and was told that it did. [I had] a hazy feeling that perhaps I should shoot this man.”

He didn’t, as without even a piece of luggage, Mutesa was flown aboard a Royal Air Force plane to Tangmere in Sussex, England. A state of emergency was declared in Buganda. The non-cooperation, which followed between Mengo and the protectorate government, forced the Governor to invite Sir Keith Hancock to head a committee that included leading Baganda to resolve the crisis.

This committee, which sat at Namirembe, led to the Namirembe Conference, which was the basis of the Buganda Agreement and Constitution of 1955. The agreement paved the way for Mutesa’s return from exile. The 1955 agreement left Buganda, and especially the Kabaka, in a weakened position. Although the colonial government agreed not to raise the issue of the East African Federation “either at the present time or while local public opinion on the issue remains as it is at the present time”, it did not rule out resurrecting the question in future.

More significantly, the agreement made the Kabaka, a constitutional monarch, spelling out the limits of his powers and those of the Lukiiko. His ministers were also given some political powers, thereby creating different centres of power. All major decisions by the Kabaka and the Lukiiko, including the appointment of ministers, would be subject to the approval of the governor.

Down but not out

Only three years later, however, another clash occurred between the Mengo and protectorate governments over the issue of direct election of Buganda’s representatives in the Legislative Council. As a result, from 1958 to 1961, Buganda was not represented. Towards the end of 1958, the appointed Lukiiko passed a resolution terminating all the agreements signed between Buganda kings and Her Majesty’s Government. They demanded that powers that had been surrendered to the crown government should be returned to the Kabaka.

The Secretary of State for Colonies, Lord Iain Macleod, met the Kabaka in August 1960 with a delegation from the Lukiiko to iron out their differences, as the country prepared for the 1961 elections that would pave the way for independence. Buganda’s response was two fold: boycott the elections and declare the kingdom’s own independence.

In September 1960, the Lukiiko submitted a memorandum to the Queen, outlining a “plan for an independent Buganda”. Under the plan, an independent Buganda would maintain friendly relations with Her Majesty’s Government, remain a member of the Commonwealth, and seek admission to the United Nations. Buganda would have her own army with the Kabaka as commander in chief.

Arrangements for Buganda’s independence were to be completed by December 31, 1960. On January 1, 1961, the Lukiiko declared Buganda’s independence. Little effort, however, was made to bring the declared independence into reality. As the Lukiiko had decided to boycott the March 1961 elections, it asked people in Buganda not to register for the elections. Some Baganda, however, chose to participate.

The two main parties contesting the elections were the Uganda Peoples Congress (UPC) headed by Apollo Milton Obote and the Democratic Party (DP) led by Benedicto Kiwanuka. Both parties shared the view that Uganda should continue as a united country. They viewed Buganda’s demands as a threat to that unity as the country moved towards independence. DP won 20 of the 21 seats on offer in Buganda. Having secured another 23 in other parts of the country against UPC’s 35, the Democratic Party formed the government headed by Benedicto Kiwanuka as Chief Minister.

The two main parties contesting the elections were the Uganda Peoples Congress (UPC) headed by Apollo Milton Obote and the Democratic Party (DP) led by Benedicto Kiwanuka. Both parties shared the view that Uganda should continue as a united country. They viewed Buganda’s demands as a threat to that unity as the country moved towards independence. DP won 20 of the 21 seats on offer in Buganda. Having secured another 23 in other parts of the country against UPC’s 35, the Democratic Party formed the government headed by Benedicto Kiwanuka as Chief Minister.

Having failed to secede and the future of the Kabaka and the kingdom in an independent Uganda being uncertain, Buganda changed strategy. It decided to push for a federal status, which would ensure the continued existence of the kingdom, and secure for the Kabaka a superior position within an independent Uganda. In June 1961, thousands of Baganda chanting “Kabaka Yekka” (only the king) staged demonstrations against the government of Benedicto Kiwanuka, whom they viewed as a traitor.

“Kiwanuka’s sins were threefold. He was a Catholic who had opposed the Protestant establishment in the Kingdom of Buganda; he had fought the [1961] election despite the boycott declared by the Kabaka’s government, he was a Muganda and a commoner who had dared to set himself above the Kabaka,” writes I.R. Hancock in the Journal of African History (1970). This anti-Kiwanuka movement led to the founding of Kabaka Yekka (KY) as a political party to fight DP and to promote Buganda’s tribal interests.

URL: https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=namukwakula

Kabaka, Obote jump into bed

At the first Constitutional Conference in London in September 1961, also known as the first Lancaster Conference, to negotiate Uganda’s independence, Benedicto Kiwanuka, as the Chief Minister, vehemently opposed the idea of having Buganda’s representatives to the National Assembly indirectly elected. He knew that DP would stand no chance of winning elections in Buganda in a process controlled by Mengo.

UPC, which had been completely beaten by DP in Buganda in the March 1961 elections, smelt an opportunity to dislodge DP from government by allying with Buganda. The UPC delegation, therefore, sided with Buganda, marking the birth of the ill-fated UPC-Buganda alliance.

In March 1962, direct elections to the Lukiiko were held in Buganda for the first time. In a deal with KY, UPC did not contest any seat. KY easily beat DP, taking 65 out of the 68 seats. Since it had been agreed that Buganda’s representatives to the National Assembly would be elected indirectly, with the Lukiiko serving as the electoral college, KY’s victory meant that DP had no chance of remaining in power.

When the April 1962 general elections were held, DP won 24 seats and UPC 37. The Lukiiko’s indirect vote handed 21 seats to KY. As agreed earlier, UPC and KY formed a coalition government with Milton Obote as Prime Minister, ahead of Uganda’s independence on October 9, 1962.

Through a constitutional amendment, a provision was made for the non-executive positions of President and Vice President, to be elected by the National Assembly. On October 4, 1963, five days before the country’s first independence anniversary, Sir Edward Mutesa was elected President and Sir Wilberforce Nadiope, the Kyabazinga of Busoga, Vice President.

From the start, the UPC-KY alliance was doomed to fail. While UPC presented itself as a national, progressive party espousing national unity, KY was unashamedly tribal and conservative, pushing for Mengo’s interests.

The only thing the two had in common was the desire to kick DP out of power. As Samwiri Karugire wrote in A Political History of Uganda (1980), “the coalition between the UPC and the Mengo government was a cynic’s delight because the two parties had divergent views on almost every conceivable subject”. It did not take long, therefore, for the two to clash.

Honeymoon ends early

Once in power, Obote started moves to weaken Mengo’s influence. Through patronage and promises of rewards, Obote got a number of KY members in the National Assembly to switch allegiances to UPC. In January 1963, UPC decided to field candidates against KY candidates for two seats in the Buganda Lukiiko but failed. Although the UPC-KY alliance prohibited UPC from opening branches in Buganda, Obote felt strong enough by early 1964 to do so. The remaining KY members considered forming an alliance with DP.

The election of the Kabaka as president had been seen as an effort to bridge the rift between Mengo and the rest of the country, but it seemed to have the opposite effect. The Prime Minister and the President were jostling for state power.

Even on seemingly trivial things, such as whose picture appeared where, became a matter of contention. The constant display of the Prime Minister’s portrait rather than that of the President when playing the national anthem on national television, for example, displeased Mutesa and his supporters.

One of the main sources of disagreement between the Kabaka and the central government was the future of the “lost counties”, which had been taken from Bunyoro and given to Buganda by the colonial authorities, as a reward for its (Buganda’s) support.

The independence constitution had provided for a referendum in the “lost counties” for them to decide their fate. But as census figures showed that the Banyoro outnumbered the Baganda in the area, Buganda was strongly opposed to the referendum.

Despite Buganda’s opposition, the Obote-led government pushed ahead with the referendum in November 1964. Having gained a majority in the National Assembly, UPC was no longer reliant on KY support.

As expected, Buyaga and Bugangaizi counties voted in favour of returning to Bunyoro. The Kabaka’s government challenged the validity of the referendum in the High Court and lost. Its appeal in the Privy Council was dismissed in April 1965. The loss of the two counties to Bunyoro sparked off angry scenes among the Baganda in Kampala.

Buganda’s Katikkiro (Prime Minister), Michael Kintu, was blamed, forcing his government to resign. Kintu was replaced with Mayanja Nkangi, a former minister in the central government, who had resigned following the collapse of the UPC-KY alliance. Whereas UPC didn’t need KY any more, a fierce power struggle was raging between Milton Obote and the newly-elected Secretary General, Grace Ibingira, for the control of the party.

Ibingira, a cabinet minister, was elected Secretary General during the UPC delegates’ conference in December 1964, in Gulu. His aim, he later claimed, was “to build resilience in the UPC against Obote’s tendency to grab all power and promote militarism”. However, some historians say that on the contrary, Obote supported Ibingira’s bid against his critic, who was then incumbent Secretary General, John Kakonge.

Whatever the truth, Ibingira emerged as Obote’s main rival, gaining the support of the Prime Minister’s enemies, including Kabaka Mutesa and Buganda Kingdom. The stage was set for the 1966 crisis. The catalyst, however, didn’t come from Buganda or even Uganda, but Zaire, as the Democratic Republic of Congo was then known.

Amin takes centre stage

In January 1966, Daudi Ocheng, the former Secretary General of KY and a close friend of Edward Mutesa, attempted to move a motion in the National Assembly calling for an investigation of Deputy Army Commander, Col. Idi Amin, over corruption. The UPC parliamentary group refused to support it. He had tried to move the same motion earlier in 1965 without success.

In January 1966, Daudi Ocheng, the former Secretary General of KY and a close friend of Edward Mutesa, attempted to move a motion in the National Assembly calling for an investigation of Deputy Army Commander, Col. Idi Amin, over corruption. The UPC parliamentary group refused to support it. He had tried to move the same motion earlier in 1965 without success.

Amin, who was seen as Obote’s confidant in the army, had been accused of involvement in gold and ivory smuggling during military operations in support of Congolese rebels in Eastern Congo. Milton Obote and some of his ministers, including Adoko Nekyon and Felix Onama, were being linked to the alleged smuggling.

Obote told cabinet and UPC parliamentarians that Amin had admitted to having large sums of money on his account, but it was money received from the Congolese rebel group to buy military supplies. The rebel group, headed by Christopher Gbenye and General Nicholas Oleng, was fighting the government of Moise Tshombe, who was seen by Obote as a traitor to the cause of African independence.

He had been involved in the assassination of Congolese independence leader, Patrice Lumumba. Obote had tried to keep support to the rebel group secret, since it had not been officially sanctioned by the government. During a cabinet meeting on February 4, while Obote and his key supporters were on a scheduled visit to West Nile, Grace Ibingira, a minister of state, mobilised his group to support the motion against Amin. Cuthbert Obwangor, who was then acting chairman of cabinet, didn’t have the numbers to block the decision. They asked Daudi Ocheng to re-table his motion.

The same day, February 4, Ocheng tabled the motion in the National Assembly. He accused Obote, Adoko Nekyon and Felix Onama of involvement in the gold and ivory scandal, along with Amin. The motion calling for suspension of Amin while investigations were conducted was adopted.

Obote interpreted the move as an attempt by Ibingira and his supporters, including Ocheng and Kabaka Mutesa, to overthrow his government with the backing of the Army Commander, Brig. Shaban Opolot. There were reports of mysterious troop movements in and out of Kampala in the following days, as the two sides sought to place loyal forces in the capital.

Gloves off in showdown

Upon his return to Kampala on February 13, Obote discovered that the Kabaka had approached the British High Commissioner seeking military assistance. He twice tried to reach the Kabaka by phone but failed. On February 15, Obote accepted to set up a commission of inquiry into the allegations against Amin, Nekyon and Onama. The commission was headed by Justice Sir Clement Negeon de L’estang of the Court of Appeal. He sent Amin on a two-week leave, short of the suspension demanded by the Ocheng motion. (In a report eventually published in August 1971, the commission exonerated Obote and the others).

While seemingly implementing the parliamentary motion, Obote also moved against his rivals. During a cabinet meeting on February 22, 1966, he arrested Grace Ibingira, the UPC Secretary General and Minister of State; Balaki Kirya, Minister of Mineral and Water Resources; George Magezi, Minister of Housing and Labour; Dr. E.B.S. Lumu, Minister of Health, and Mathias Ngobi, Minister of Agriculture and Co-operatives.

The following day, he promoted Amin to take over the army command and moved Shaban Opolot to the newly created post of “military adviser” to the cabinet. To complete the coup against his own government, Obote suspended the 1962 Constitution, removing the Kabaka from the presidency and assuming all powers. In April 1966, Obote convened the National Assembly and had the changes ratified without debating the new Constitution. Obote became the executive president, with John Babiiha as his Vice President.

Baganda members of the National Assembly refused to swear allegiance to the new constitution. It was also rejected by the Lukiiko, a day after its adoption.

On May 20, 1966, the Kabaka’s government issued an ultimatum to the central government, ordering it to leave Buganda soil by the end of that month. Buganda chiefs were called upon to stir up rebellion in their respective areas while a number of Baganda flocked to the Kabaka’s palace in Mengo. Obote reacted by declaring a state of emergency in Buganda on May 23.

The following morning, on May 24, police was called in to intervene in the chaotic situation around the Kabaka’s palace. Later in the day, the Minister of Defence, Felix Onama, asked Obote to authorise the deployment of the army to “restore order”.

Obote sent in the army under the command of Idi Amin. He stormed the palace, overpowering the Kabaka’s guards who attempted to put up resistance. During the fighting, the Kabaka escaped by climbing over the wall. He fled to England through Rwanda. For a second time, Buganda’s conflict with the central government had ended with the Kabaka being forced into exile.

Who should be blamed for the 1966 crisis? To most Baganda, the answer is obvious: Milton Obote. However, some writers have pointed out that other actors, notably Kabaka Mutesa and his confidante Daudi Ocheng, the Mengo government and the Lukiiko, the ambitious Grace Ibingira, and even the tactless Benedicto Kiwanuka, should all share in the blame.

As historian Phares Mutibwa has written in Uganda Since Independence (1992), “In the final analysis, the issue between Mengo and the central government was the basic constitutional one of where power actually resided: in a local unit (Buganda) or with the central authority (Obote’s UPC government). Personalities came into the story merely as catalysts.”

The 1995 Constitution may have tried to answer the question, but it certainly didn’t answer it to the satisfaction of all parties, hence the current tussle between President Museveni and Kabaka Mutebi.

opusml@yahoo.co.uk

Buganda Kingdom : background

Buganda is the largest traditional kingdom within Uganda (the others are Toro, Ankole and Bunyoro, which make up part of the Western Region). During the colonial period, the British allowed the Kabaka (king) of Buganda and the rulers of the other states a large degree of power and influence, and this was retained a little while into independence. The kingdoms were abolished by Milton Obote in the 1960's but have recently been revived by President Yuseveni's government as a way of bringing government closer to the traditional feelings of the people.

Roy Stilling, 14 September 1996

When Uganda became independent, Milton Obote became prime minister. Being from the small Langi tribe, he appointed King 'Freddy' Mutesa II, Kabaka of Buganda, as president of Uganda. As has been mentioned, the Baganda were the largest ethnic group and more anglicized (by contact with missionaries and the colonial authorities) than the other groups.

By appointing Mutesa, Obote miscalculated. He alienated other tribes and didn't actually succeed in placating the Baganda, who by May 1966 were openly agitating for Obote's overthrow. Obote used the then deputy commander of the Army, one Idi Amin to do the dirty work. Amin personally attacked the Kabaka's palace with a 122 mm gun mounted on his (Amin's) personal jeep. The King escaped and fled to Britain were he died in (I think) the early 1970s. Later, of course, Idi Amin staged a coup against Obote. Ironically, this was initially welcomed by the Baganda (naturally, Amin blamed Obote for their persecution).

Stuart Notholt, 15 September 1996

The Buganda Kingdom history of flags:

The current flag of the Buganda kingdom comprises three equal vertical stripes of blue, white and blue, with the kingdom's logo placed in the centre of the flag on the white stripe:

Marius Korsnes stands in front of a solar cell plant in China during one of his study trips to China. Photo: Private

Marius Korsnes stands in front of a solar cell plant in China during one of his study trips to China. Photo: Private Solar cells are now being built in rural areas, too. Photo: Marius Korsnes

Solar cells are now being built in rural areas, too. Photo: Marius Korsnes This photo shows offshore wind power in Rudong – a rapidly growing industry. Photo: Marius Korsnes

This photo shows offshore wind power in Rudong – a rapidly growing industry. Photo: Marius Korsnes

The statistics of the Struggle for the resource of land in Uganda

The statistics of the Struggle for the resource of land in Uganda

This is the second part of our special series on the tug of war between Buganda and the central government, putting this year's bloody clashes and the continuing stand-off in a historical context. The first part showed how the current conflict is uncannily similar to the clashes of 1966 and 1953. In this part, HENRY LUBEGA takes a closer look at how Kabaka Edward Mutesa fell out with the colonial authorities, and then with the Obote government, with disastrous consequences for king, kingdom and country:

This is the second part of our special series on the tug of war between Buganda and the central government, putting this year's bloody clashes and the continuing stand-off in a historical context. The first part showed how the current conflict is uncannily similar to the clashes of 1966 and 1953. In this part, HENRY LUBEGA takes a closer look at how Kabaka Edward Mutesa fell out with the colonial authorities, and then with the Obote government, with disastrous consequences for king, kingdom and country: The two main parties contesting the elections were the Uganda Peoples Congress (UPC) headed by Apollo Milton Obote and the Democratic Party (DP) led by Benedicto Kiwanuka. Both parties shared the view that Uganda should continue as a united country. They viewed Buganda’s demands as a threat to that unity as the country moved towards independence. DP won 20 of the 21 seats on offer in Buganda. Having secured another 23 in other parts of the country against UPC’s 35, the Democratic Party formed the government headed by Benedicto Kiwanuka as Chief Minister.

The two main parties contesting the elections were the Uganda Peoples Congress (UPC) headed by Apollo Milton Obote and the Democratic Party (DP) led by Benedicto Kiwanuka. Both parties shared the view that Uganda should continue as a united country. They viewed Buganda’s demands as a threat to that unity as the country moved towards independence. DP won 20 of the 21 seats on offer in Buganda. Having secured another 23 in other parts of the country against UPC’s 35, the Democratic Party formed the government headed by Benedicto Kiwanuka as Chief Minister. In January 1966, Daudi Ocheng, the former Secretary General of KY and a close friend of Edward Mutesa, attempted to move a motion in the National Assembly calling for an investigation of Deputy Army Commander, Col. Idi Amin, over corruption. The UPC parliamentary group refused to support it. He had tried to move the same motion earlier in 1965 without success.

In January 1966, Daudi Ocheng, the former Secretary General of KY and a close friend of Edward Mutesa, attempted to move a motion in the National Assembly calling for an investigation of Deputy Army Commander, Col. Idi Amin, over corruption. The UPC parliamentary group refused to support it. He had tried to move the same motion earlier in 1965 without success.

The Ankole tribesmen on military parade

The Ankole tribesmen on military parade

City streets are blocked up against moving traffic in the city. Any one who goes to the city does so at his or her own risk.

City streets are blocked up against moving traffic in the city. Any one who goes to the city does so at his or her own risk. The business shops in the international city are closed up.

The business shops in the international city are closed up.

The Inspector General of the Uganda Military Police Force, Kale Kayihura has paid up his supporters and they are threatening to lynch prosecution lawyers outside the Courts of Law. Photo: @micoh

The Inspector General of the Uganda Military Police Force, Kale Kayihura has paid up his supporters and they are threatening to lynch prosecution lawyers outside the Courts of Law. Photo: @micoh